Launching the Future at Mitsubishi Shipbuilding

MHI’s oldest business is turning itself into one of the most modern. Back in 1884, the group that became Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) started by building ships. More than 140 years later, Mitsubishi Shipbuilding remains a core part of MHI and is developing advanced technology that allows us to build specialist vessels ourselves and offer sophisticated engineering and design services to peers.

By pioneering next-generation ships, particularly those powered by and transporting low-carbon fuels, we believe we can carve out a profitable niche in a cyclical and intensively competitive industry – and demonstrate that there is a viable future for Japan’s shipbuilding sector as a whole.

At first glance, Japan appears to fall between two stools: the large, state-supported shipyards of China and South Korea, whose economies of scale give them a price advantage of 20% or more; and the specialist constructors of Europe and the United States, who developed the technologies we are all still using and have strong brands and long-standing customer relationships.

On closer examination, however, our sector has its advantages too. We have continued to develop the technology we originally licensed in; we have built a strong domestic supply chain; and Japan’s shipyards have a natural customer base in the extensive network of coastal shippers that transport about 40% of the nation’s industrial goods as well as very strong oceangoing ship operators and shipowners. This ecosystem is remarkably flexible and promotes cooperation alongside competition. I believe these factors give Japan an advantage at a time when technological change in our industry is accelerating.

Technology as a Service

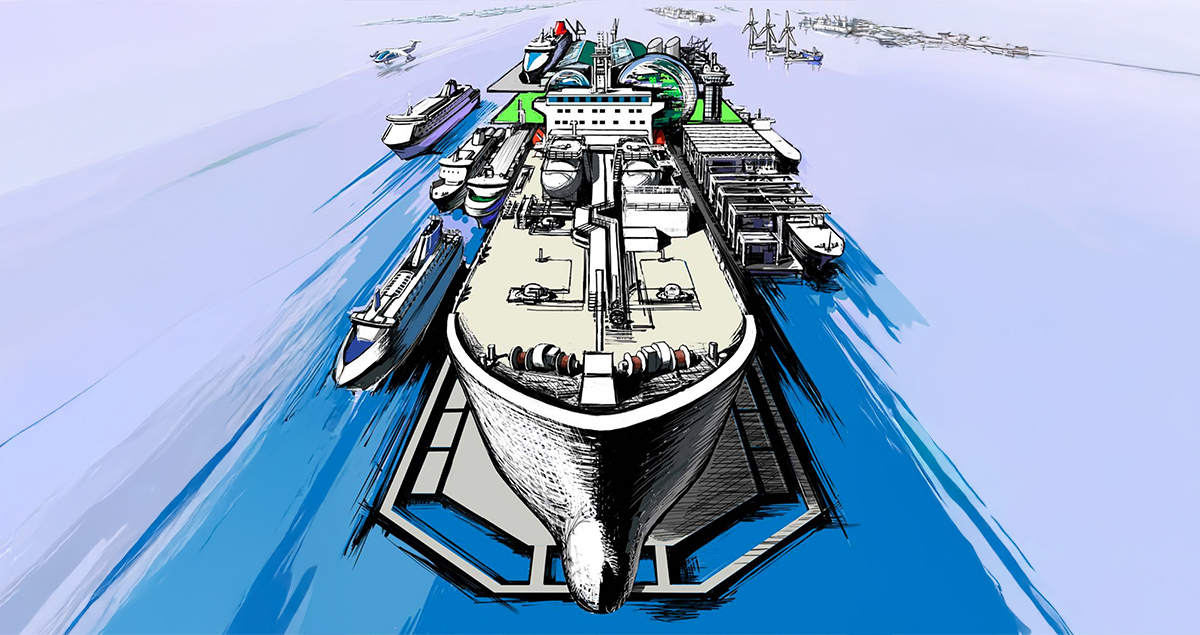

As the most technically focused of the country’s half a dozen major shipbuilders, Mitsubishi Shipbuilding is determined to lead this change. We are doing so by focusing on two strengths. First, the construction of specialist vessels, from roll-on, roll-off ferries to coastguard patrol ships, research vessels and cable-layers that can help connect offshore wind farms to the onshore electricity grid.

While the need for such ships is limited – the company builds only five or so a year -- their design and construction is technically very complex. Not only does this mean we can be profitable on numerically small orders; their complexity requires us to keep refining our technology and honing our skills – to the point where they have become institutionalized.

The key example here is gas handling. Although we no longer build large-scale LNG carriers, we have the knowledge to design and construct (or manage the construction of) a new generation of alternative fuel ships that represent a large segment of shipping’s future: liquid CO₂ carriers, methanol and ammonia-fueled ships and LNG/ammonia bunkering vessels, for example.

This brings me to the Mitsubishi Shipbuilding ’s second strength. To make the most of the skills we had built up, we launched an engineering and design business in 2012 to complement our construction activities. This division can design entire vessels or their key components, including fuel storage tanks and LNG and ammonia fuel-handling systems. We are also prototyping an onboard CO₂ capture and storage system.

At the same time, we have developed a proprietary engineering software system called MATES, as well as 3D-Viewers, a program to easily visualize ships as they are being designed.

Mitsubishi Shipbuilding is the only shipyard in Japan that has these capabilities, not least due to synergies with other parts of the MHI Group. Our sister company Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Marine Machinery & Equipment Co., Ltd., for instance, manufactures turbochargers for marine engines, propellers, fin stabilizers and other specialized components that we incorporate into our designs.

Turning peers into partners

As a result, we are able to offer a wide range of products and services, including fueling systems for ship’s engines using future low-carbon and CO₂-free fuels and vessels in general. Moreover, we offer our products and services not only to end customers but also to other Japanese shipyards and even, potentially, for foreign partners – as demonstrated by our recent collaboration with Elomatic, a Finnish marine engineering firm.

This strategy is benefiting from growing demand for alternative fuel vessels and clean propulsion systems as the shipping sector tries to meet demanding decarbonization targets and improve its economic security. This means the value of our technological capabilities will continue to increase.

Of course, our rivals in Asia are also moving into the market for eco-friendly vessels. But Japan is determined to become the number one in this sector. The strong ecosystem and long history of cooperation among our nation’s maritime sector that I have mentioned can help us achieve that, allowing us to standardize designs, components and methods of working. Continued investment, such as the company’s new quay and crane rail extension at its main Shimonoseki yard, as well as into digital transformation and automation, are essential. And so is clear government guidance and support.

In some cases, mergers may be the Japanese shipbuilding sector’s way forward. For example, Imabari Shipbuilding announced its decision to increase its equity stake in Japan Marine United (JMU), effectively making it a subsidiary. If realized, this move would create the world’s fourth-largest shipbuilding group by construction volume, which should significantly enhance its competitive strength. In other instance, deep collaboration may be more productive. Mitsubishi Shipbuilding, for example, might be the best candidate to design a vessel, while one of our peers may be more efficient in actually building it.

Either way, I am confident that despite all the challenges facing us, we will play an important role in the future of MHI as specialist shipbuilding will grow into a successful industry for Japan.

![]()

Learn more about Mitsubishi Shipbuilding