Finding the 'X' factor for deep decarbonisation

"Electrify everything".

That was the advice energy and climate writer David Roberts gave Vox readers in a piece published little over a year ago, as the best possible strategy the world could take for solving climate change.

His logic? Thanks to the rise of renewables, electricity is now the easiest way to generate zero-carbon energy. It's also a quick way of decarbonising the energy use of entire households, streets, and even cities.

In short, "electrify everything" should be the mantra engineers the world over should be adopting, Roberts argued.

It's a catchy slogan, but as Roberts himself notes, it's not as simple as it sounds. Electricity grids running solely on renewables have to handle massive swings in generation, where demand may be way above or below the power being produced by the wind or sunshine on a given day or night.

One way to solve this issue is to ramp up the "dispatchable load" on the grid, the energy demand that can be controlled or scheduled to take advantage of peaks and troughs in general demand. For example, surplus renewable electricity can be stored in car batteries until it is needed or used to drive heat pumps that can heat space or water for use later, the article suggests.

But is storing all that excess power as simple as that? Not according to Professor Emmanouil Kakaras, senior vice president and head of power and energy solutions at Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems (MHPS) Europe, a part of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Group.

He argues that electrification plus battery storage and dispatchable load techniques can only ever be part of the solution to the intermittency issue. "If you add all the pieces together, and you are very ambitious about electrification and electromobility, and you exhaust all the limits of space heating or using all the heat pumps you can imagine and so on, the point is that in a massive deployment of renewables, you still will have a bit of mismatch between demand and supply, which is significantly higher than the two sectors - power-to-heat and battery storage - could accommodate," he tells BusinessGreen.

In other words, there will still be excess clean electricity going to waste. Meanwhile, it's simply not yet feasible to electrify everything. You only have to look at the (very nascent) efforts to develop electric aircraft to realise the challenges of switching some major global industries over to electric power.

It's not just aviation: shipping, chemicals, cement and steel production are all deeply difficult areas to electrify, and therefore to decarbonise. It's a point highlighted in the most recent report from the influential Energy Transitions Commission, which concluded in November that heavy industries could be decarbonised by mid-century, but only with the help of hydrogen, carbon capture systems, and advanced biofuels, alongside electricity.

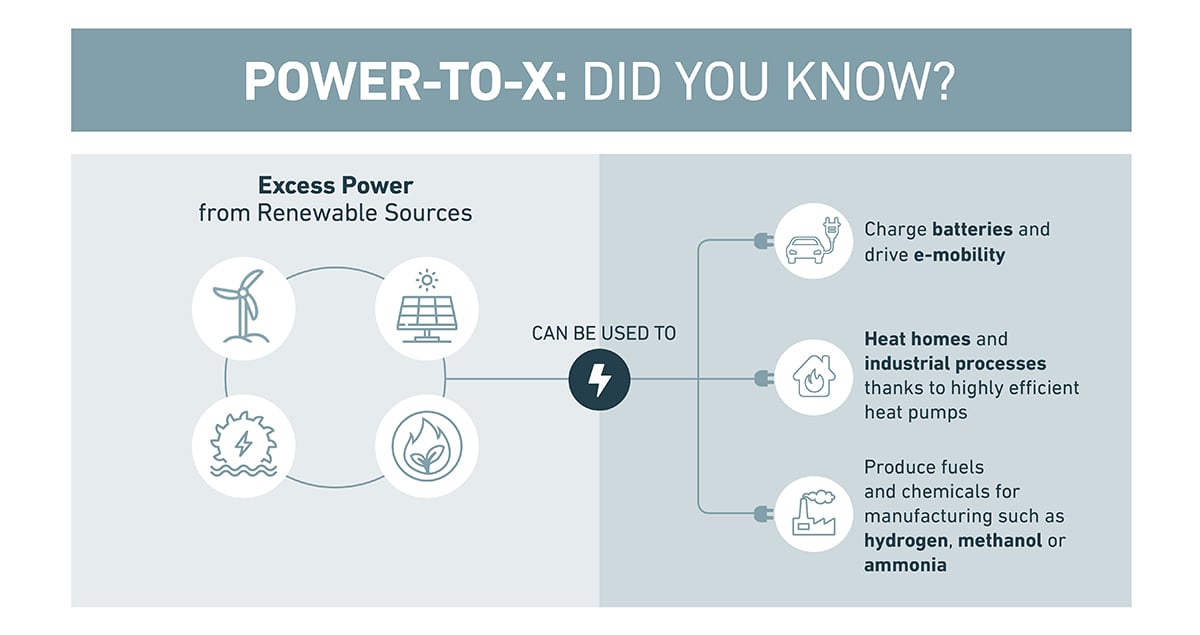

According to Professor Kakaras, the key to deep decarbonisation will lie in our ability to harness the excess electricity from national grids to decarbonise these hard-to-electrify sectors. It's a strategy he calls 'Power-to-X', where 'X' electricity is converted into another form of latent energy.

For example, Power-to-X could describe turning electricity into hydrogen, or synthetic biofuels, or thermal heat. "There is a variety of technologies," he says. "There are obvious solutions where these technologies make sense immediately. For instance you can today put a large electrolyser in a refinery and use renewable hydrogen there. There are other cases where a more complex solution would be required, such as a power-to-liquids approach."

Provided the electricity is generated with renewables, converting excess power to fuels such as gasoline emits 90 per cent less carbon than gasoline produced through conventional means, according to Kakaras.

Net zero emission targets are hitting the headlines, following the launch of the EU's draft 2050 climate strategy that sets out a target for net zero emissions across the trading bloc by mid-century, and the UK government's own investigation into the potential of a net zero target. Moreover, the IPCC's stark warning back in October that net zero emissions will be required worldwide by 2050 if we are to avert the worst effects of climate change has inevitably focused minds.

But such economy-wide decarbonisation will be impossible without applying a Power-to-X strategy, argues Professor Kakaras. "In the case that you would like to move towards more ambitious targets, such as 80 per cent decarbonisation or beyond, then you by definition need a high degree of decarbonisation that could only be reached through this Power-to-X approach," he says.

However, it is possible to achieve such a net zero vision using technologies that are already available to us. "We are far beyond research," Kakaras notes. MHPS Europe is already working on scaling up the Power-to-X solution, particularly with hydrogen and carbon dioxide utilisation. Being part of MHI Group, a wide variety of technologies also complement this endeavour. "We consider ourselves one of the pioneers of the hydrogen economy," says Kakaras. "We have developed new gas turbines that are able to utilise large amounts of hydrogen, but we have also technologies for the production of hydrogen. That might be either electrolysis or through the decarbonisation of natural gas. That means you can have a thermal path to generate hydrogen as well, from natural gas with subsequent carbon capture and storage."

He continues: "In the middle of this value chain, we have a number of conversion technologies which are coming from our chemical engineering technologies, which can be put together and practically service the whole value chain from hydrogen production, subsequent conversion, CO2 separation, synthesis, up to the end use. So, this is for us a unique opportunity to offer more to the value chain in that context."

But to really kickstart the Power-to-X revolution, the next few years needs to see a roll out of first-of-a-kind projects across a range of sectors, to prove that the technology can work at scale and to enable costs to come down. Regulatory barriers also need to be snipped away, including unnecessary charges on electricity storage, Kakaras argues.

New revenue streams will also have to be identified, which won't necessarily be based solely on the price of the green product or the benefit of the CO2 avoided. Compensation for ancillary grid services, for example, could also play a part. But a strong carbon price would go a long way to motivating private sector action, Kakaras admits. "For the heavy industries, a stronger price signal would speed up the decarbonisation needs, and this of course improves the business case of power-to-fuel," he says.

The hope is this engineering vision can come together to help deliver a new generation of investment in Power-to-X technologies by the mid-2020s, Kakaras explains, which in turn will help to shape a new era of business where cross-sector collaboration - between utilities and fuel suppliers or process industry, say - is a common occurrence.

Ultimately though, the success of these technologies depends on the will of countries to deliver deep decarbonisation. "If for any reason societies intend to hold the brake and say we have done enough in terms of decarbonisation, and there is no need to further deepen the carbon abatement, then these technologies will never fly," warns Kakaras. "They fly because societies are committed to decarbonisation."

With warnings about the consequences of doing nothing on climate change growing ever starker, many are optimistic that decarbonisation is quickly becoming solidified as the only acceptable long-term trajectory for economies the world over. Eventually, the emerging narrative is that net zero emissions will become the default destination. But to get there, it won't be as simple as electrifying everything. We'll need other technologies to bring the 'X' factor.