Wearable scanners will be able to read our minds

This year, a San Francisco-based start-up hopes to demonstrate a scanning device that could revolutionise the diagnosis of cancer and heart disease — and, eventually, read our minds.

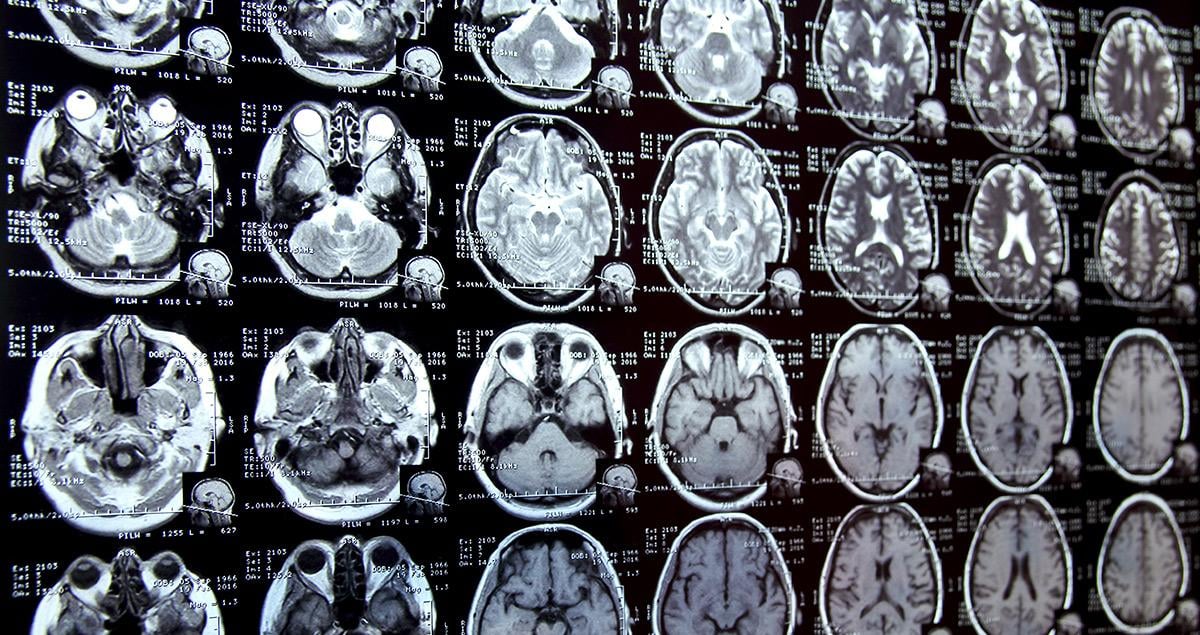

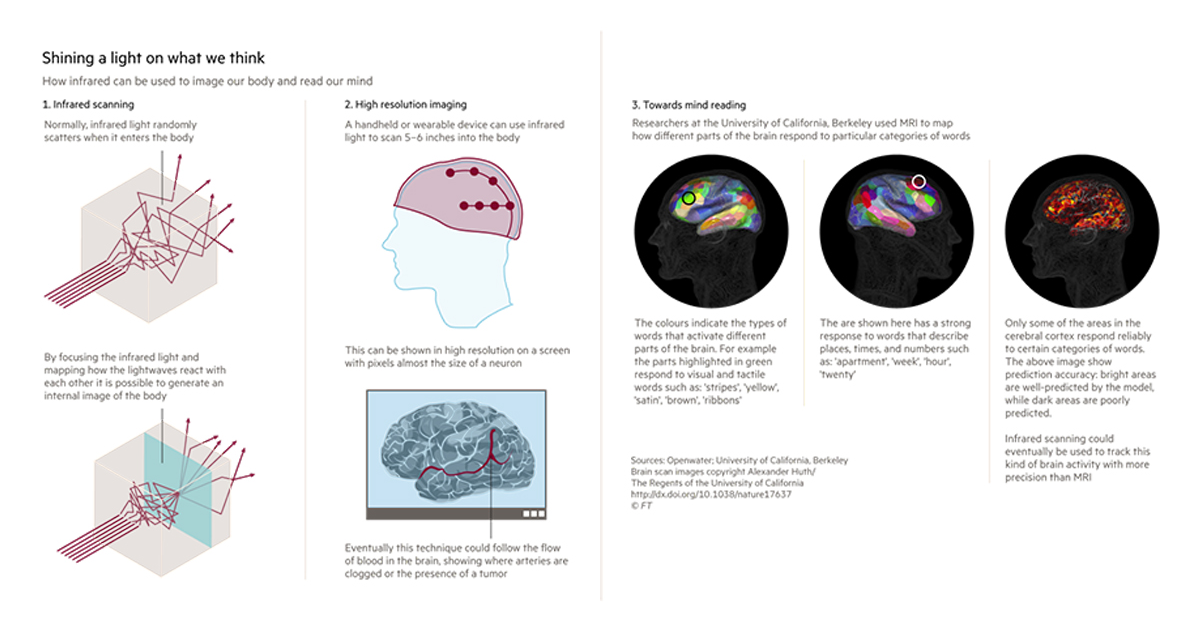

The new device will do the same job as a Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) machine, but Openwater, the start-up, promises it will be cheaper and more accurate. Using infrared light, the handheld gadget can scan five or six inches deep into the body, reporting what it sees to the focus of a micron — the same size as a neuron.

The tool can be used to spot a tumour by detecting the surrounding blood vessels and to see where arteries are clogged. One day, it could follow the flow of oxygenated blood to different areas of the brain, tracking our thoughts and desires.

“It is a thousand times cheaper than an MRI machine and a billion times higher resolution,” says Mary Lou Jepsen, founder of Openwater, the start-up. “That’s a lot of zeros.”

The device benefits from three scientific breakthroughs. First, the shrinking of the size of pixels on display screens to almost the size of the wavelength of light. It can detect small changes in the body and beam them back at high resolution.

Second, the device makes use of physics that has been “known for 50 years but is only really available in research labs”, Ms Jepsen says. This physics focuses on the ability to assess scattering of light, so it can map how waves interfere with each other.

Imagine you drop two rocks in a puddle. Then, as the ripples spread out, they interfere with each other, changing the way the water moves. Light waves behave similarly when they bounce off objects. By tracking the patterns in reverse it is possible to see the size, shape and location of the objects that they have hit.

The third breakthrough is in neuroscience, with developments that help us understand where the brain is active by looking at where the oxygenated blood flows.

Ms Jepsen, formerly of Google and Facebook, is expert in holograms and pixels and she has personal experience — she suffered from a brain tumour herself. She spent a decade as an engineer researching the obscure area of holograms, living on $800 a month.

When she developed a brain tumour, she needed to find a job with good health insurance. She went into consumer electronics and became a world-class mastermind at producing screens with ever more pixels. In her last job, at Facebook, she worked on virtual reality. She recovered from her brain surgery, but she never lost her interest in the inner workings of the brain.

Researchers have already been able to use MRI to guess what people are looking at. The University of California, Berkeley paid graduate students to lie in MRI machines and watch YouTube videos for hundreds of hours, watching how their brains behaved depending on what they saw.

Then, it showed the students new video clips and was able to roughly replicate the images they saw. Openwater is aiming to show brain activity at a far higher level of detail, down to individual neurons, making this kind of mind-reading more precise. If the company can produce a mass-market consumer product, it would also give neuroscientists far more data for building brain maps.

Ms Jepsen expects the device will have little trouble gaining approval from that US Food and Drug Administration because it uses near infrared imaging, which has been used in medical devices for decades.

There is a bigger debate to be had, however, about the ethics of mind-reading. Ms Jepsen says that mind-reading is inevitable and she is keen to engage the public on the issue before devices that enable it are created. Openwater believes it will be key for users to own their own data, so that they can delete it at any time and set conditions for its use. “I think that’s super important,” Ms Jepsen says.

With the right rules in place, however, mind-reading has great creative potential, she argues. “We think of things in our brain that we can’t get out in the form of speech or in the form of moving our fingers to type and I think we could unlock so much more potential if we could communicate visual and auditory thoughts directly out of our brain,” she told the FT’s Tech Tonic podcast.