The gadget wizard

Index

Shortly after the U.S. Civil War, a mysterious Japanese doll departed from Japan and made its way to the United States. Believed to have been created some time in the 1840s by a mechanical genius named Hisashige Tanaka, the female doll was clad in an ornate kimono. Driven by an intricate wind-up mechanism, the doll wielded a calligraphy brush to write on a piece of paper mounted on a board in front of it. Rediscovered in the U.S. in 2003, it was subsequently returned to Japan and underwent restoration.

The creator of this amazing doll lived in an era when a feudal Japan made its emergence from two centuries of enforced isolation, to embark on a policy of open diplomacy and rapid industrialization. Son of a tortoise-shell craftsman, Tanaka was born in Kurume City, Chikugo province (presently the southwestern part of Fukuoka Prefecture) in 1799 and began showing signs of genius from an early age. While still only nine years old, Tanaka had created a trick pencil case that no one could open. He studied mathematics and astronomy in Edo (Tokyo), Osaka, and Kyoto. His imagination and dexterity led to a number of amazing inventions, such as the mujinto, a light that was 10 times brighter than a candle.

Sometimes called “The Thomas Edison of Japan,” Tanaka had an ability to produce amazing devices, which earned him the nickname “Karakuri Giemon” a word that does not lend itself well to direct translation but might be rendered in English as “The Gadget Wizard.” “Karakuri,” meaning a gadget or gimmick, derives from the word karakuru, an archaic verb that originally meant to manipulate objects horizontally or vertically using strings. Now it is generally used to mean the mechanism that drives a machine.

Mothers of Invention

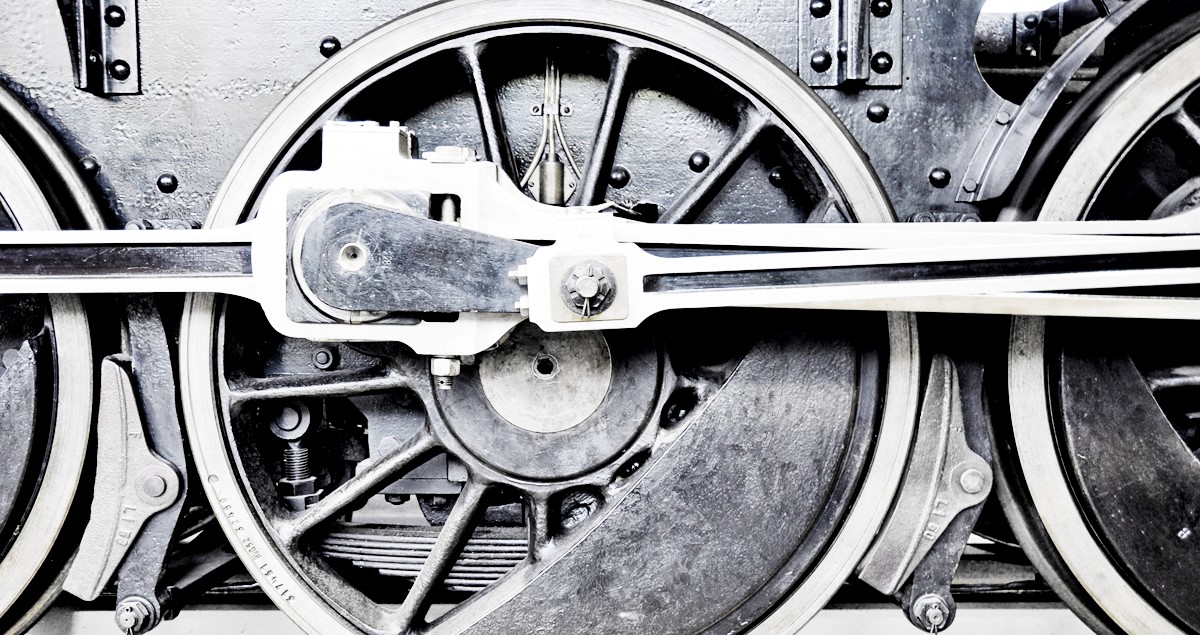

Hisashige Tanaka possessed an innate ability to grasp the workings of machines. After viewing a steam locomotive aboard a Russian ship in Nagasaki harbor, he built a steam locomotive prototype and two steamboat prototypes, making subsequent improvements to his original design until he built a working steamship. Tanaka later went on to found Tanaka Seizo-sho, a forerunner of the present-day electronics giant Toshiba Corporation.

The urge to invent goes back to the dawn of human civilization, and surprisingly sophisticated mechanical devices existed even in ancient times. A “South Pointing Chariot,” a type of mechanical compass developed in China, is said to date back to 2600 BC. Clepsydra, or water clocks, first appeared in 1,500 BC in ancient Babylon. Both eventually reached Japan. The “Nihongi,” an ancient history of Japan, records that Emperor Tenchi produced a water clock in 671. By the Heian Period (794-1185), mechanical dolls, which appeared on floats in festival processions, had begun made their appearance.

The “Konjaku Monogatari” (Tales of Times Now and Past), a 31-volume collection of Japanese folklore compiled around 1120 A.D., contains the story “How Prince Kaya Made a Doll and Set it Up in the Ricefields.” As the story relates, Prince Kaya (794-871) a son of Emperor Kanmu (781-806), was an extraordinarily skilled craftsman who made a mechanical doll in the shape of a boy about four feet tall, which was “a splendid device, and the Prince was praised to the skies for his ingenuity and skill.”

During the Edo period (1603-1868), several individuals around the country, such as Benkichi Ono of Kaga province (Ishikawa Prefecture), Isoshichi Iizuka of Mutsu (Aomori Prefecture) and the aforementioned Hisashige Tanaka, became famous for their amazing craftsmanship. These men were preceded by Hanzo Hosokawa. A native of Tosa, present-day Kochi Prefecture on the island of Shikoku, Hosokawa lived from 1741 to 1796.

Hosokawa had originally been interested in astronomy, but also mastered mathematics and physics. But his real claim to fame rests on his amazing mechanical devices, one of which the “Chahakobi Ningyo” (tea-serving doll) may very well be the world’s oldest mechanical robot particularly if “robot” (a term derived from the 1921 play “Rossum's Universal Robots,” by Czech author Karel Capek) is used in its original sense of a machine that performs menial work. This little karakuri inspired the development of numerous clockwork dolls capable of complex movement, which delighted the aristocrats of old Edo.