Shipping has to raise its eco-stakes - here's how

Index

Shipping is the main carrier of worldwide trade, transporting 90% of all goods. It is highly likely the screen you are reading this on made its way to you by sea.

Despite this, the industry produces less than 3% of all CO2 emissions.

However, with the global economy expected to grow by 130% between now and 2050, shipping emissions are projected to soar as global trade increases.

According to the International Maritime Organization (IMO), CO2 emissions from the shipping industry could increase by anything between 50% and 250% by 2050.

And CO2 is not the only environmental challenge the industry faces. Shipping also needs to control the amounts of other harmful substances it releases into the atmosphere, in particular nitrogen oxides and sulfur oxides.

To counter this, shipping companies are seeking out both alternatives to the heavy fuel oils used by most freight carriers, and ways to strip noxious particles from vessels' exhaust gases.

Borne by gas

One of the most obvious alternatives to heavy fuel oils is Liquefied Natural Gas.

LNG is already used as fuel by more than 80 vessels around the globe, and the numbers are growing.

This is largely due to the near-zero levels of sulfur oxides emitted by LNG vessels compared with diesel-powered ships.

Sulfur oxides have been linked to health problems such as respiratory disease and environmental phenomena such as acid rain. The shipping industry has sought to cut its SOx emissions by introducing restrictions in key shipping routes across the world.

So far, the IMO has introduced four Emission Controlled Areas, ranging from the Baltic Sea to the coasts of North America, with a sulfur cap of 0.1%. This 0.1% cap also applies throughout the EU.

In 2020 new IMO regulations will come into force mandating the sulfur content of marine fuels in all waters of the world to be less than 0.5%.

Ships have two options to bring their limit sulfur emissions within these limits.

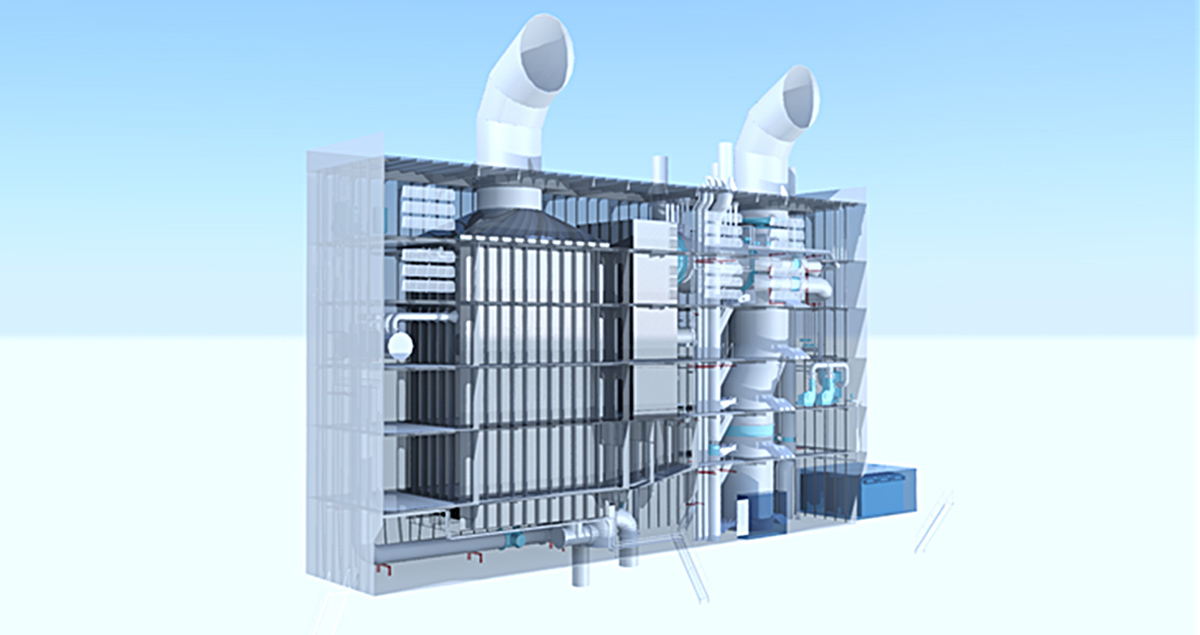

Firstly, they can install desulphurization equipment, such as the Large-scale Rectangular Marine Scrubber developed by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Group. It removes SOx from the exhaust gases emitted by marine diesel engines, purifying emissions from inexpensive heavy fuel oil to a level equivalent to more expensive low-sulfur fuels.

The second option is to use fuels with a lower sulfur content, such as LNG.

As well as cutting a ship's SOx emissions, LNG also has lower nitrogen oxide and CO2 emissions, making it a popular choice for shipping companies seeking to reduce their environmental impact.

However, the growth of LNG as a shipping fuel is limited by a lack of infrastructure for fueling -- or 'bunkering', as LNG fueling is known.

There are currently only a dozen ports around the world offering LNG bunkering, and most of those are based in Europe.

While more bunkering stations are planned, a major breakthrough came earlier this year when world's first purpose-built LNG bunkering vessel began operating from the Belgian port of Zeebrugge.

The ENGIE Zeebrugge will carry out ship-to-ship bunkering across northern Europe. While LNG-fueled ships have, up to now, been largely dependent on fixed bunker locations or the limited bunkering capacity of LNG trailers, ENGIE Zeebrugge will be able to service a variety of LNG-fueled ships. Its operator Gas4Sea aims for it to be the first in a fleet of LNG bunkering vessels.

Going electric

Although using LNG as alternative to diesel does have advantages, there are also drawbacks.

Not only is it dependent on widespread bunkering infrastructure, but it is also more polluting than diesel when it comes to one particular greenhouse gas: methane.

To avoid increasing methane emissions -- which are 30 times more potent than CO2 for trapping heat in the atmosphere -- some shipping operators are looking to emulate the motor industry's move to electric vehicles.

Boats used electricity before diesel: the Bergen Electric Ferry Company in Norway began operating in 1894. Its last boat with electric propulsion was converted to use petrol in 1926, and later used diesel.

However, in 2015 the company returned to its roots and once again operated an electric ferry, powered by 12 5kWh lithium-ion batteries. The ferry runs all day and charges its batteries all night.

The rapid advances in lithium-ion battery technology, pioneered by the motor industry, has put the spotlight on electricity as a potential fuel source for shipping.

However, regular night-time charging is not an option for the many shipping liners travelling long distances, and the battery technology does not yet exist that offers these vessels the power they need.

One solution, again with a nod to the motor industry, may be hybrid electric vessels.

Norwegian shipping company Eidesvik Offshore, which already runs its ships with LNG, this year successfully retrofitted a battery system to its vessel Viking Princess.

Viking Princess now runs on a combination of a battery pack for energy storage and three LNG-fueled engines. The batteries are estimated to have cut Viking Princess' fuel use by nearly a third, and its emissions by 18%.

Shipping, which was once powered by nothing more than the wind, is not yet the truly renewably-fueled transport it once was. But it is sailing in the right direction.