Japan is joining the new space race – here’s how

Fifty years after the first moon landing, Earth’s closest celestial neighbor is within our sights again.

As part of its Artemis mission, NASA aims to send robotic explorers to our natural satellite from 2021 and expects humans to follow them back to the moon as early as 2024.

But the moon is just one small step in the greater scheme of things: NASA aims to use what it learns from establishing a long-term presence there to take the next giant leap for mankind: a human mission to Mars.

Unlike 50 years ago, this new moonshot is not a two-horse race between Russia and the U.S. Players as diverse as India, Japan, China, and the United Arab Emirates are among those joining the fray with their own space exploration programs.

Japan joins the new moonshot

As well as these countries driving their own programs forward, there will be significant international collaboration. Europe will be closely involved in Artemis, and Japan is among those that have joined forces with NASA.

An agreement signed in fall 2019 laid the foundations for NASA and Japan’s space agency, JAXA, to work together on missions to the planned lunar space station, Gateway, and to the moon itself.

Japan has a long history of space collaboration to bring into this partnership: it has sent several astronauts to the International Space Station (ISS), provided the station's “Kibo” laboratory and robotic arm, and has been carrying out regular resupply missions to the ISS.

The groundbreaking plan for a more permanent presence on the moon, as a foothold for an onward leap to Mars, presents Japan’s researchers and technologists with a few new challenges.

Packing a punch

Take deliveries of provisions and equipment as an example: Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) is currently one of four regular suppliers to the ISS.

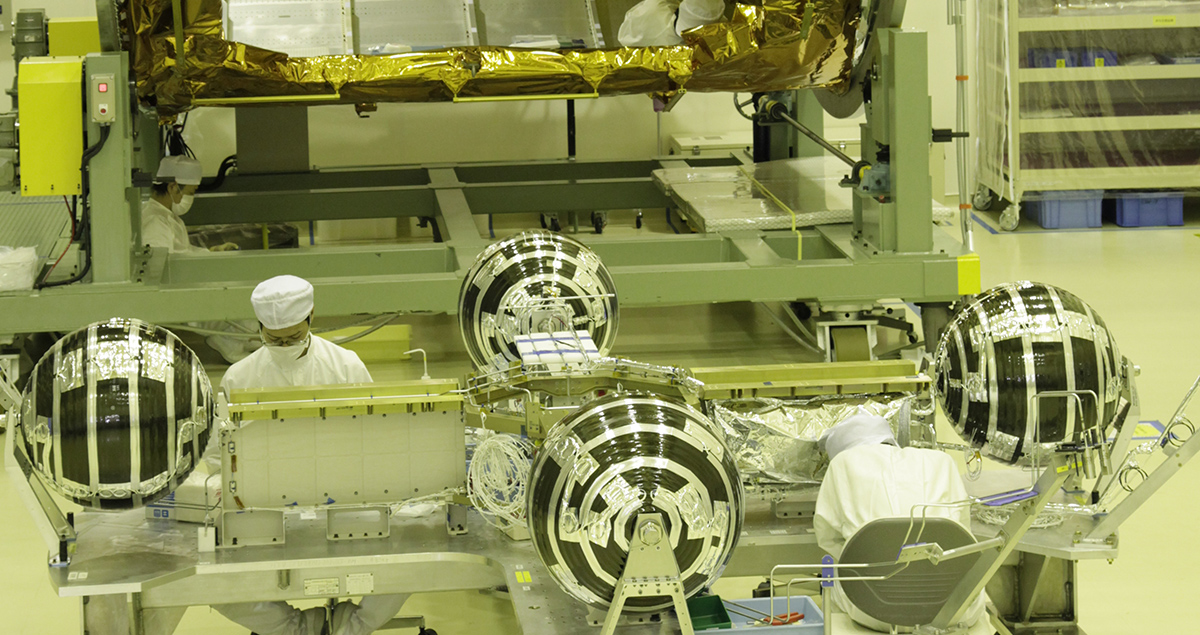

Its H-II Transfer Vehicle (HTV), known as ‘Kounotori’ (white stork), delivers food, clothes, scientific materials for onboard experiments, and large hardware to the ISS. Launched into orbit by one of MHI’s H-II rockets, it carries a payload of around six metric tons to the station, and takes away the station’s refuse on its way back.

To offer the same services for the new space station and lunar base will mean that greater distances and payloads will need to be catered for.

MHI is in the process of upgrading both Kounotori and its new H3 launch vehicle to pack a punch when it comes to supplying the Gateway and the moon surface over the next decade.

Space freight

A new model of the Kounotori ‘space freighter’, HTV-X, is under development. It will enhance cargo transport capability up to about 50%, readying it for trips with more supplies and missions further out in space as the Artemis program unfolds.

At the same time, the H3 launch vehicle, which will halve the manufacturing cost compared with earlier launch vehicles, is set to make its maiden flight by early 2021. Different versions of H3 and HTV-X will be geared for different orbits, depending on the size of the payload being carried.

Over the next few years, MHI and JAXA will work on optimizing H3 and HTV-X for different types of missions to Earth’s orbit, the moon, and beyond.

By 2030, MHI expects a “heavy” variant of H3 to be ready to carry payloads of up to 12 metric tons to the moon. This could include rovers, habitation modules, and supplies for a future lunar base.

With a Japanese mission to the Martian orbit already on the cards, it is entirely conceivable that, in another 50 years, there will be men and women on the moon or Mars patiently waiting for weekly provisions delivered by Japan’s interstellar workhorses.

Learn more about MHI Group’s broader portfolio space development activities and other services that support the research community.