How to build and maintain trust: learning from the Japanese experience

This article was previously published on World Economic Forum's blog and in our newsletter, if you're not already a subscriber, sign up here.

When it comes to economic growth, corporate profitability and innovation in software and services, Japan has had little to teach the world over the past 30 years. But if we turn to issues such as trust, stability and social cohesion, perhaps there are some useful learnings to be drawn from the Japanese experience.

Considering the theme of this year’s World Economic Forum meeting of “Rebuilding Trust”, it is noteworthy that Japan has almost wholly avoided the growing social divisions and surge in political populism that rising inequality has inflicted on so many developed economies.

Most experts attribute this breakdown in trust, correctly in my view, to the erosion of high-skilled jobs in the manufacturing sector and a consequent stagnation in middle-class incomes in the West, while the richest segment of society has continued to see rapid gains in wealth.

Japan has avoided such a polarization for several reasons. The country’s challenging demographics have actually been a blessing in this respect: in the context of a declining workforce and, latterly, a declining population, it has been possible to eke out small increases in GDP, particularly in terms of GDP per working age population, against a background of what has effectively been economic stagnation.

The outsized older generation has also been spending its accumulated wealth, or transferring it to children and grandchildren, thereby supporting consumer demand while ameliorating, to some degree, the underlying economic disparity. Also on the demand side, Japan has successfully expanded inbound tourism.

All of this means that, up until now, Japan has managed to more or less maintain its level of prosperity without having to compensate for its decreasing population with the large-scale (and sometimes unplanned) immigration that has further inflamed populism in the US and much of Europe.

Thinking collectively

Even more importantly, however, Japan has stuck firmly to its collective ideals. With society remaining largely homogenous it has also remained largely cohesive, preserving beliefs that elevate the group over the individual and contribute meaningfully to social stability.

The experience of a lack of growth, and even of relative decline when measured internationally, has been a collective one – everyone has been in the same boat. Japanese people prize equity and fairness above liberty and as long as most are treated equally, the rare rich person or star can be accepted: “they live in a separate world from me”, is the typical reaction.

This has allowed Japan to tolerate 30 years of stagnation with barely a social or political ripple – not something that would have been possible in the west, in my opinion. Of course, the country has paid a price in terms of innovation and entrepreneurship, both of which remain limited, and hence in absolute levels of economic growth. However, this is a tradeoff most Japanese are content with.

It is hard to apply lessons from this experience to what are very different societies in other parts of the world. However, paying more attention to community values and embracing your responsibilities toward other groups in society are worthwhile aims – and perhaps worth examining rather than dismissing just because they have been associated with Japan’s ‘lost decades’.

Human capitalism in action

Western companies have, indeed, started to elevate such holistic ‘stakeholder’ thinking over the last few years, toning down many years of a shareholder-first approach. This approach, which I like to call ‘human capitalism’, is already widely practiced in Japan.

Indeed, I believe that the main success of Japanese corporations in recent times – to the extent that they have been successful – has been based on a considerate management style. The worst thing you can call a Japanese manager is “inhumane”, which explains why our executives generally do not hire and fire staff pro-cyclically; why they are cautious when it comes to selling or spinning off divisions, however ‘non-core’; and why we often take a long time to make decisions and to integrate acquisitions.

While such tactics have been routinely derided by western competitors, they have allowed Japanese managements to maintain a much greater level of mutual trust with their employees as well as a social license to operate in their communities – giving them a real edge.

There has undoubtedly been a short-term cost in terms of operating performance. But internal consensus and stability allow long-term strategic thinking and bold commitments. Think of the early investments of Japanese trading firms in south-east Asia; the blue-sky research carried out in the engineering, materials and chemicals sectors; or the painstaking attention to detail and continuous improvement common across Japanese industry.

Tackling decarbonization

At Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, some of the investments into clean technology that we made decades ago are only now starting to really pay off, as we try to accelerate world efforts at decarbonization, specifically by developing infrastructure to produce and scale clean hydrogen and to capture store and utilize carbon dioxide (CCUS).

Moreover, we are relying not only on the rich engineering heritage developed over almost 140 years of corporate history. We are also building financial and entrepreneurial networks worldwide, investing in innovative start-ups, collaborating with academia and sharing knowledge and proprietary technology with a range of partners.

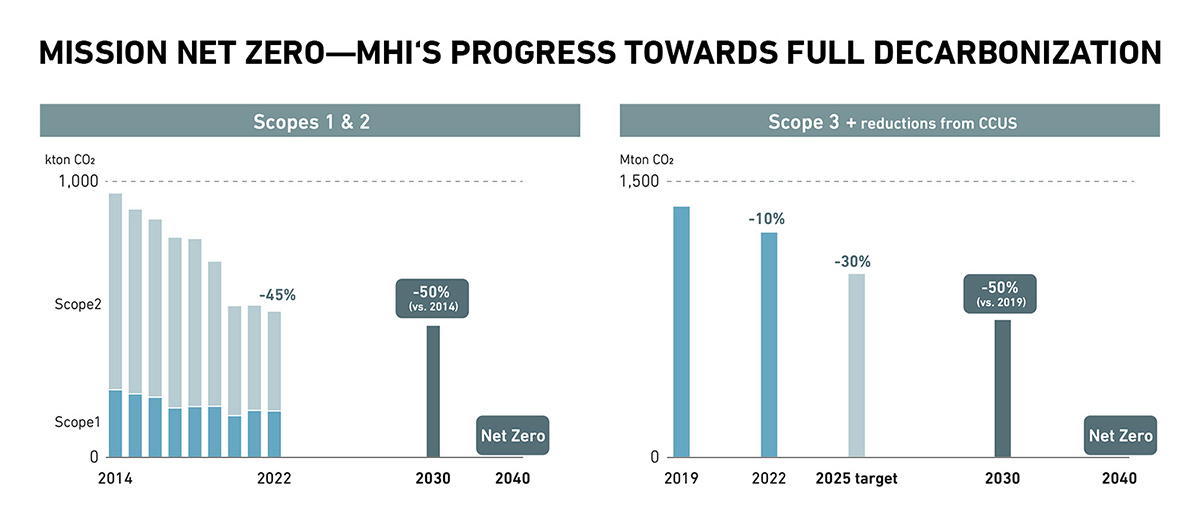

And we have made a bold promise of our own, MISSION NET ZERO, committing to decarbonize our Scope 1, 2 and – significantly – our much larger Scope 3 emissions (including reductions via CCUS) by 2040. We believe that as a low-carbon technology supplier we must decarbonize a decade before our customers.

In a similar manner, Japan as a nation has promised to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, despite all of its natural and geographic disadvantages as an island with few energy or mineral resources and a lack of suitable land for developing renewables.

As has hopefully become clear, once the Japanese people commit to a goal, they are determined to achieve it -- a mindset that is rooted in the collective desire to contribute to the group’s success. When it comes to reaching net zero, I am optimistic that we will make good on our word, while continuing to act in a way that merits the world’s respect and trust.

Read more about MHI's MISSION NET ZERO